The nineteenth-century author and flâneur Stendhal once wrote that the best way to experience a new place is to wander aimlessly in whatever direction that whim dictates. Without planning and without knowing beforehand, the cognitive faculties turn acute, and the senses sharpen as they are being constantly surprised by the surroundings. This is what happened to me in Regensburg. But that was not my plan from the beginning.

Ever since I went to Innsbruck last year, in the footsteps of my study object, Latin professor Vilhelm Lundström and his students, I have waited for an opportunity to go to Regensburg. Lundström and his disciples undertook their Grand Tour in 1909, with a three months’ stay in Rome, and a “historical-philological” course, led by Lundström, as their ultimate goal. But Rome does not begin in Rome, as any student of classical Antiquity would know. Regensburg was the first stop on their trip, as the northernmost city of the Roman empire of old, on the very border along the Danube. After months of preparation, the students were now about to encounter actual Roman remains for the first time in their lives. Their second stop was Innsbruck, then the Brenner pass and the Alps, Sterzing, Verona, and Firenze, and after ten days of travel, the group finally reached Rome. Last year in Innsbruck, I stayed at the same hotel as they did, the Goldener Adler, almost as old as the Roman empire itself, at least one of the oldest still operating hotels in Europe.

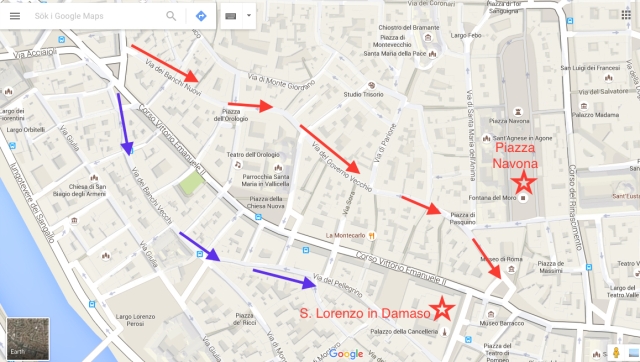

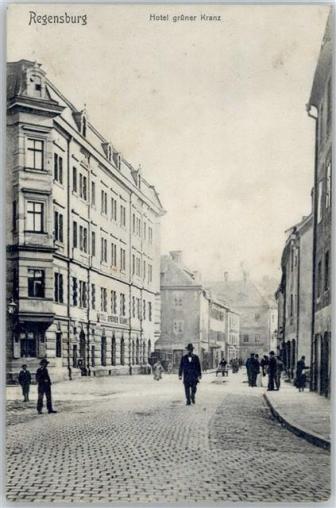

But I had to see Regensburg, too. I had read about it in Lundström’s travel report, and in some of the students’ writings. They had arrived in the afternoon (4.10 pm, to be exact), and stayed at hotel “Grüner Kranz” in Obermünsterstrasse, rather close to the railway station. And in the dining room of the hotel, the first lecture of the course had taken place. Directly afterwards, the group went out to town to inspect the Roman ruins of the old Castra Regina: Porta Praetoria, built in 179 CE, the only remaining Roman gate of its kind north of the Alps except for Porta Nigra in Trier. Among Lundström’s private papers in the Regional State Archives in Gothenburg, I had even found a postcard with Porta Praetoria on it, which Lundström had sent to his mother at home in Sweden. Before leaving Regensburg, the group also visited the small historical museum of the city – at that time located in the so-called Alte Pfarre of the church of St. Ulrich – and studied the collections in what Lundström described as a “bothersome cold”.

Hotel Grüner Kranz in an old postcard.

Lundström was a master of suggestion and emotion when it came to the study of history. The students witnessed about how, in Regensburg, he affectionally stroke, almost caressed, the wall of Porta Praetoria with his bare hands while demonstrating it that afternoon in March 1909. These images have remained with me – the postcard with the gate, and the thought of Lundström’s hands on it. The north and the south. The present and the past. And Lundström, who now also belongs to the past. I had to see the gate. I arrived in Regensburg in the evening on a late train. It was dark, and the cold temperature was more than just bothersome, it was almost unbearable. I took a quick walk down to the Danube but did not dare to go very close on the icy quay. The water murmured, wide and unruly, and a few lights from the medieval Stone Bridge glistened in its black surface. Close by, I almost stumbled upon Porta Praetoria, but decided to save my encounter with it until the next day. Now I knew that it was there, down by the river.

Porta Praetoria on the postcard that Vilhelm Lundström sent to his mother in 1909.

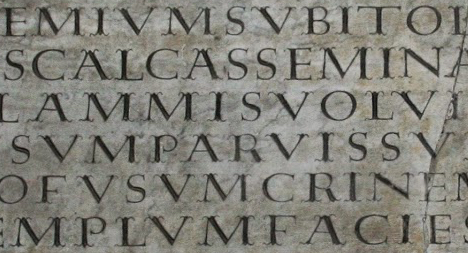

Next day was equally cold and also windy, which produced tears in my eyes and made the skin of my face ache as I went out. First, I passed by the “Grüner Kranz” – I already knew that it had long since ceased to be a hotel. A tap dance school was housed in its basement. But then I decided, all of a sudden, to do a Stendhal. Sooner or later I was going to the gate, and to the historical museum, but before that I felt like to just roam the small streets and see where they took me. I was in no hurry. A park near my hotel in the outskirts of the city centre belonged, as I had seen on the map, to the castle of Thurn und Taxis, a Bavarian princely family. The park, behind a fence, looked magical. Stern, large trees, here and there a small round-temple, even a sculptured sphinx lay among the trees in the snow. The daylight was hazy. The park was empty. Signs on the fence indicated that the park was included in a museum housed in parts of the Thurn und Taxis castle. Perhaps I could get in? I followed the fence until I came to a medieval church, St. Emmeram, around which the castle had been constructed in a later period, according to information outside. The church was open. I went in. It was empty apart from another curious party of two persons. Now, I decided to do not only a Stendhal, but also a “in Santa Croce with no Baedeker”, as in E. M. Forster’s “A Room with a View”: to experience the church without bothering to look up any information about the objects in it. I often find historical sightseeing and museums boring – I get tired feet, I lose oxygen, I feel trapped in a structure forced upon me, and this kills my natural curiosity. But this park, and this church, I had stumbled upon by chance, and only my curiosity, led by my five (or six) senses, had drawn me to them. And I was struck by beauty. Every stone or wooden face on every figure in the church came alive and looked at me. Every ornament was full of emotion. Every Latin inscription was talking to me from the walls – and curiously enough, many of the inscriptions started with a friendly Viator! “Hey, Traveller!” or Viator amice! “Oh, Traveller Friend!” That was me. The enchanted viator. The friend.

The Orphee.

The Thurn und Taxis museum turned out to be open only on weekends during winter season. One could enter the properties – as a small Vatican state, with no unauthorized vehicles allowed inside – but the museum entrance was firmly closed. But I did not care, since I had made no plans. Part of the magic about the park was, I reflected, just the fact that it could only be viewed from outside, by the Viator, the Traveller and the Outsider. I continued my sorgenfrei-way through the tiny city centre of Regensburg, and again I was lucky. A restaurant that had caught my attention only through its beautiful name – Orphee – turned out to be a century-old French bistro, once founded by the Hungarian Baron Aloys Finkelstein-Korntheur in an old brewing house belonging to the Thurn und Taxis family. The dark wooden panels, the small marble tables, the art noveau lamps – little had changed inside the restaurant during the last century. After lunch, I was finally ready for Porta Praetoria. But first, I went down to the river again. In daylight, it was actually blue, but the murmur of the quickly flowing water was the same as the night before. The power of the river seemed enormous. The border of the Roman Empire. No trespassing beyond these waters. The wind hit harder than ever on the bridge, and I had to wrap my scarf around my face on the way towards the city gate.

Some objects and sights struck you as of a different size than expected. Colosseum, for example, was much smaller than what I had anticipated the first – and only – time I went inside it. The Porta Praetoria experience was the other way around. It was so much larger and imposing than what the small postcard image had let me believe. The blocks of stone were huge, in stark contrast to the smallish scale of the modern city centre (with “modern” I mean basically “medieval”). The eastern tower and the western of the two arches remained, later built into a house complex, but, as I read on a sign next to the gate, it was not until in the 1890’s that the later structures were torn down and the gate was revealed. Only a couple of decades before Lundström’s journey! I was filled by a sudden joy, standing under the worn arch of the gate. I was in Rome, and I was not. I was joined with history and yet I was present, in the present. Everything seemed to exist at the same time, entangled, and yet I felt free. I removed my glove and put my right hand upon the stone wall. It felt cold. A bothersome cold. I smiled and went away to get my luggage at the hotel and, just like Lundström and his students, took the train to Rome.